Planes parked idly on runways. Borders shut. Once bustling streets and shops are eerily empty and quiet. Travel has come to a halt as the Covid-19 pandemic rages on relentlessly.

In envisioning a post-pandemic world, many conversations have been focusing on rethinking the future of work and rebooting ravaged economies. An important but often missing theme is reimagining the way we travel.

Tourism Growth in ASEAN – A Victim of Its Own Success?

Among other factors, a booming middle class, proliferation of low-cost carriers, and increased air connectivity have resulted in an increase in the number of visitors to ASEAN. In 2019, ASEAN recorded 133 million tourist arrivals, a 7% increase compared to the previous year. According to the World Tourism Organization, the total international visitors to ASEAN is estimated to hit 152 million by 2025 and 187 million by 2030.

A growing tourism sector contributes to GDP and economic growth. Travel and tourism accounted for 12.1% of Southeast Asia’s GDP in 2019, second only to the Caribbean at 13.9%. For Thailand, Southeast Asia’s second-largest economy and most visited country, the tourism industry made up about 20% of its economy last year.

Besides creating jobs, revitalizing local businesses and drawing capital investments, tourism facilitates cross-cultural exchanges and a better understanding of societies, thus strengthening empathy and people-to-people relations.

However, the adverse impact of unfettered tourism is slowly being felt. Famous pristine beaches in the region are affected by environmental degradation caused, in part, by a surge in tourism. In 2018, the Philippines government shut Boracay for six months for environment rehabilitation. Maya Bay in Thailand has been closed to tourists since 2018 to restore the marine environment after years of unchecked mass tourism led to the destruction of corals. Indonesian authorities are imposing a US$10 tourist tax on foreign visitors to Bali to protect its environment.

[insert BBC News video “Maya Bay: The beach nobody can touch”; link here]

Source: BBC

Sustainable Tourism: An Imperative

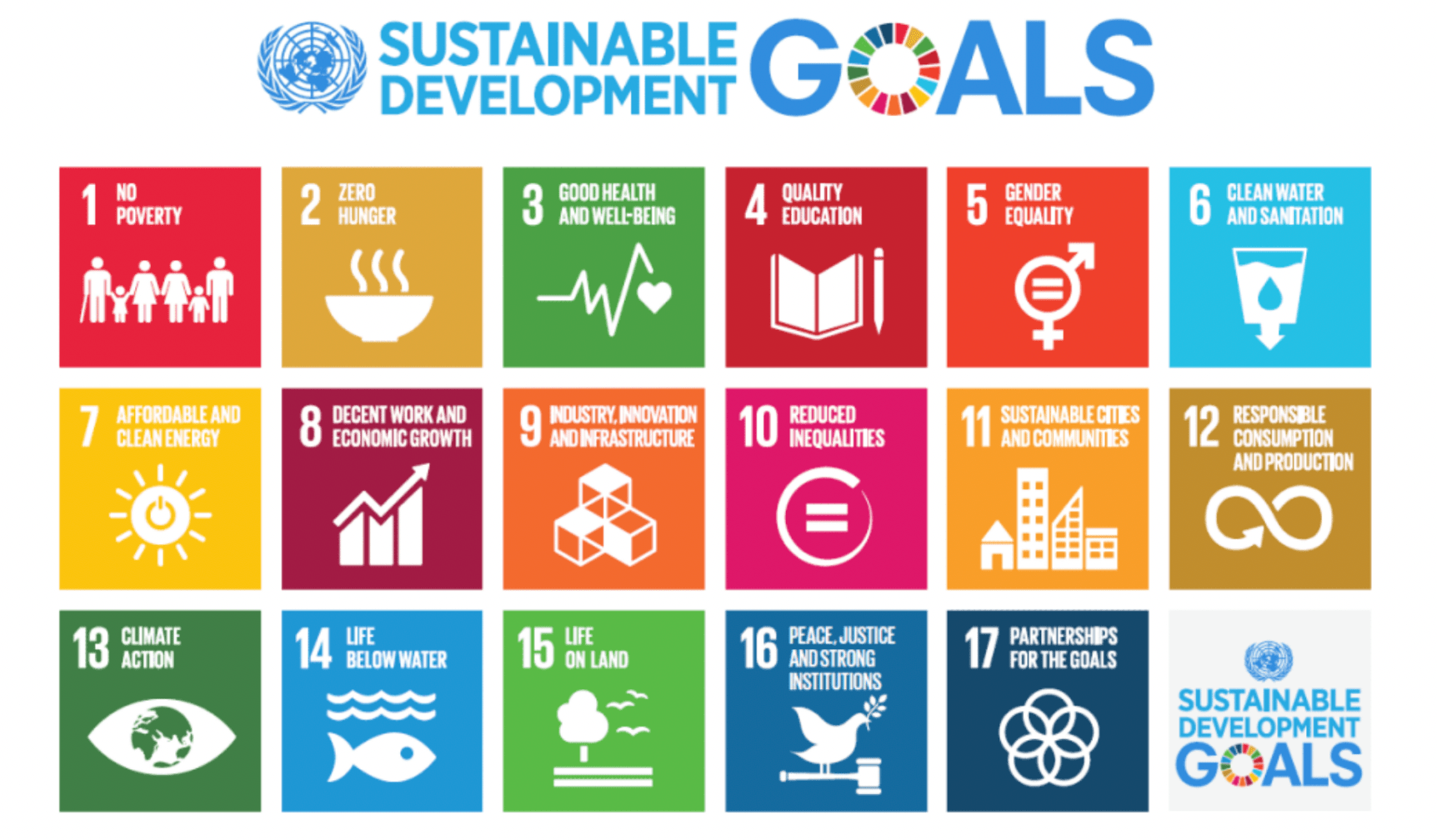

In recent years, “sustainability” or “sustainable development” has become a buzzword. In 2015, 193 UN Member States officially adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Although tourism is not explicitly included as one of the SDGs, it is interconnected – directly and indirectly – to all the SDGs. Consider the cross-cutting impact of rural communities offering homestay accommodation to tourists to generate or supplement income on Goal 1 – No Poverty and Goal 8 – Decent Work and Economic Growth. Or, to bring in more tourists, industries may accelerate building safe and reliable infrastructure such as transportation systems (Goal 9) and ensuring supplies of clean water (Goal 6).

What is sustainable tourism? It is defined by the World Tourism Organization as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host communities.”

In other words, tourism-driven growth should not be achieved at the expense of the well-being of people and the planet.

An ASEAN Solution

Recognizing this, the ASEAN Tourism Strategic Plan 2016-2025 outlines the vision for ASEAN tourism: “By 2025, ASEAN will be a quality tourism destination offering a unique, diverse ASEAN experience, and will be committed to responsible, sustainable, inclusive and balanced tourism development, so as to contribute significantly to the socio-economic well-being of ASEAN people.”

Actions to ensure sustainable tourism development in ASEAN under the strategic plan include prioritizing protection and management of cultural and heritage assets, and increasing awareness and responsiveness to environmental protection and climate change.

Specifically, some of these involve undertaking impact assessment of existing cultural and heritage sites in ASEAN, sharing best practices, revising guidelines to incorporate environment and climate change mitigation, adaptation and resilience, and continuing dialogue with relevant official bodies and stakeholders.

You Can Play a Part

You may be wondering – how can we, as young individuals, do our part in striving towards sustainable tourism?

Here are some practical and non-exhaustive travel guidelines to live by. Every action, no matter how small, can make a difference.

- Consider domestic tourism (which can be just as rewarding as international travel). There could be interesting sights and tastes in your own backyard that you have yet to discover. Good for your wallet, too.

- Do your research and choose airlines, accommodation and tour operators that are certified in, or committed to, sustainable practices.

- Choose taking public transportation over renting a private car to minimize your carbon footprint, where possible. Walking and cycling are healthy and affordable ways to discover the nooks and crannies and hidden charms of a locality.

- Travel to popular destinations during the off-season to reduce the strain on the infrastructure and environment.

- Respect and follow local regulations to preserve its culture and environment.

- Buy carbon offsets to compensate for your carbon footprint by reducing emissions elsewhere.

- Engage in education and advocacy.

One of the silver linings of Covid-19 is that it has given the natural environment a respite. In some areas, the air is cleaner, murky canals are clearer, and wildlife has returned to its natural habitats. An unprecedented time such as this also offers us an opportunity for introspection. Let’s travel in a meaningful and sustainable manner and leave behind a world worth exploring for the generations after us.

Written by Josephine Lee

Josephine is a content writer for ASEAN Youth Organization. Born and bred in Singapore, she is curious about history, cultures and languages. Besides being fluent in English and Mandarin, she speaks a smattering of Japanese and Korean. An aspiring sustainability professional, she believes the grass is greener where you water it.

Cart is empty

Cart is empty